Spain FIFA World Cup 2022 - Tactical Story

- Tactical Observer

- Jan 6, 2023

- 27 min read

Whilst Spain’s World Cup campaign will have ended more prematurely than they would have hoped, in their four games in Qatar there were a number of interesting, and repeated, tactical features of their play, in particular (and probably unsurprisingly) when they had the ball.

Spain averaged the highest possession percentage of all 32 teams at this World Cup with 75.8%, according to FBRef.com. Note - this may be a higher possession percentage than what FIFA report due to their new 'contested state' metric.

Now, aiming to control possession - and the game - is not exactly a surprising or unknown insight of the Spanish national team but as they had a lot of the ball in this tournament, this post will aim to provide in-depth observations into what they did with it. More specifically, how Spain set up to control the ball (and game), what they did with the ball in different phases of play (and most importantly reasons as to why) and (albeit with the benefit of hindsight) what they could have done differently / varied against Morocco - the team who eliminated them on penalties following a goalless draw.

This post will initially cover Spain's in possession structure and shapes, in different phases of play, as this is the base from which all of their tactical features are executed from. Then, some of the specific tactical features which will be covered are;

(Click on any of the hyperlinks to skip direct to that section, including my conclusion)

Within this piece, there will be references but not a specific section on Spain's rest defence and counterpress. Whilst it's fully appreciated that their rest defence and counterpress are key principles that help Spain maintain their control of games (to help regain possession quickly), the main observations of these aspects of their game is 'sprinkled' throughout other areas.

This also applies to Spain's out of possession set-up - due to the fact that, apart from the Germany game, and short periods within other games, Spain did not spend that much time without the ball in this tournament. However, to at least reference their out of possession principles, in addition to their rest defence and counterpress (their most used defensive tactics), without the ball, Spain were very active. They utilised the energy of their players in advanced areas e.g. Asensio, Torres, Olmo, Pedri and Gavi, to put pressure on the opposition to prevent ball progression. Behind these first lines of defence; Busquetes, their fullbacks and central defenders, were primed to jump up, if the opposition broke the first lines of engagement. When in a mid or low block, Spain tended to get into a 451 shape, where they tried to remain compact. But this is a piece about Spain, the best way to defend is to not give the ball away...

So to kickoff this post, let's look at how Spain set up when in possession...

Structure and Shape

Spain's structure and shape would vary and transition depending on the phase of play.

The below animation showcases how their default 433 structure would be staggered in their build up play, before transitioning and then varying once possession was progressed through the thirds.

As you can see in the animation, once Spain had controlled possession in the middle third, they could vary between a 4-1 base with a staggered forward line of five, and also a 2-3 base with a staggered forward line of five. (It is worth noting, that whilst the difference between these two bases were very subtle - and at times, the difference between the two could be argued either way - there did seem to be a clear intentional difference in what horizontal line their fullbacks played on - whether closer to the centre backs or midfield pivot - depending on the opposition's out of possession set-up and/or pressing scheme(s). More hypotheses will be provided on this later on in the post.)

An additional observation of Spain's structure in middle third possession was that they often formed a midfield diamond, with Asensio dropping to form the tip, to try and create numerical overloads in central areas.

As Spain progressed the ball into the final third, their predominant shape was 235, with a flatter forward line of five, but even within this shape, they executed a number of positional interchanges - which again, will be covered further down.

Across Spain's four World Cup games, they only faced a regular active high press / block against Germany. In their other games against Costa Rica, Japan and Morocco, the opposition were much more passive when Spain had the ball in their own third and instead preferred to drop into a mid block, allowing Spain more unopposed build up as they progressed possession into the middle third.

This point is backed up by FIFA's post match summary reports. Here are some of the relevant metrics from each of Spain's four World Cup games, with the Germany game highlighted to showcase the difference.

Fixture | Build Up Unopposed % | Opposition High Press % | Opposition High Block % |

Costa Rica | 42% | 5% | 3% |

Germany | 32% | 13% | 7% |

Japan | 52% | 3% | 1% |

Morocco | 53% | 1% | 1% |

Therefore, versus Germany, Spain required a few build up tactics to progress the ball through the high press / block. So whilst intricate build up play / patterns were not a regular requirement of Spain at this World Cup, to try and provide the full Spain 'tactical story', in the dropdown tab below I'll briefly (subjective) cover what Spain tended to do when they had possession in their own third for those interested - but as not really required in any of their other World Cup games, feel free to skip and read on if you prefer.

Read more detail on Spain's build up play versus Germany ↓

In build up, Spain would use their goalkeeper as an additional outfield player to help create numerical overloads in their own box and also provoke the opposition into pressing, thus leaving gaps to be exploited behind. Their defence and midfield played on different horizontal lines which helped create angles and further overload opportunities to help play through, and disjoint, the opposition high press / block. Higher up the pitch, in their forward line, the wingers stayed high (up against the opposition last line of defence) and wide to try and pin back the opposition defence, and their centre forward would initially take up an advanced central position but would also drop short to exploit spaces behind the opposition midfield line following an attempt to press, by offering a vertical passing lane. In Spain's game versus Germany, a number of their build up tactics involved playing out via their left-hand side and then switching to their right flank (Germany's weak side following an attempt to press). This focus on playing out via their left-hand side is backed up by FIFA's post match summary report which showed in the passing network section that Simon made 25 passes to Laporte compared to 11 to Rodri. This Simon to Laporte pass was Spain's 2nd highest of their player to player passing combinations, accounting for 4.6% of all Spain's total team passes in this game.

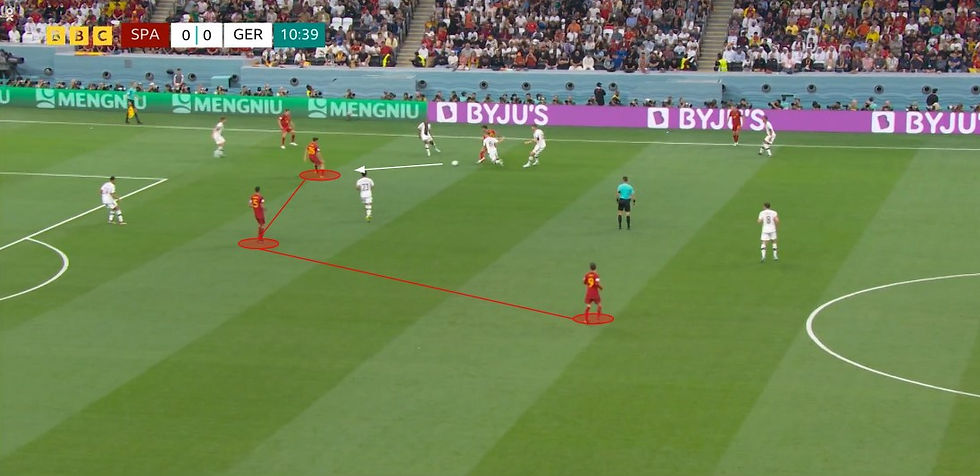

Here are some specific build up examples Spain used in this game to beat the Germany 4231 high block. In this first example, Spain have played the ball back to their goalkeeper which has triggered the Germany high press. To help them play out, their centre backs have dropped into their own box to offer a horizontal passing angle in front of the Germany 4231 high block shape (Muller leads the line, behind him Gnabry and Musiala play right and left respectively and Gundogan centrally, near Busquets). As you can see via the direction of the pass from the goalkeeper, they are going to try and play out via their left-hand side.

In the next image below, you can see that the Spain left fullback (Alba) has dropped deeper (note the difference in grass colour between the image above and below) and wider to offer a passing angle from Laporte (left sided centre back) - this triggers Gnabry to react and try and get out to him quickly. In this image you can also more clearly see the three Spain central midfielders. Note the difference in movements with Pedri moving towards the play and Gavi advancing higher. (Whilst this is a result of the play being build up on the left-hand side, it is also a common theme through other parts of Spain's play that will be covered elsewhere in this piece.)

After receiving the pass out wide, Alba carries the ball up the touchline for a short distance. (Presumably) this is to give Kimmich a decision, as whether to stay inside with Pedri or provoke him to pull wider and prevent him from progressing further up the touchline. After provoking Kimmich to pull out wide towards him, Alba makes a quick, inside horizontal pass in to Pedri who immediately lays a first-time pass back to Laporte who has followed the line of his original pass. Also in the image below, you can now see Asensio (circled in yellow) beginning his movement into the space that Kimmich has vacated (due to trying to execute his role in Germany's high press) to help give Spain a numerical advantage in their own third, and more specifically, in that deep left-hand side area of the pitch.

Now the next image below, nor this description, will give any true justice to the subtle, decoy opposite movements Pedri makes to create a passing lane for Laporte in to Asensio. However, to at least explain the actions - after laying off the pass to Laporte, Pedri begins to jog backwards (facing Laporte) which drags Kimmich back with him, then after Laporte controls the ball with his left foot and shifts it onto his right foot to shape as if his next intended pass is to be inside, both Pedri and Asensio make simultaneous movements. Pedri makes a sharp movement towards Laporte (but importantly at an angle so not to close off the vertical passing lane) to drag Kimmich up and inside and Asensio pulls into the now created vertical passing lane to receive the ball, through-the-lines, from Laporte. After receiving the pass, Asenscio lays the ball out to Alba who is now in space on the touchline, as both Kimmich and Gnabry has been dragged back-and-forth as a result of this play.

In the penultimate image below, firstly picking up on the next action in the sequence, after receiving the ball out wide, and consequently drawing both Kimmich and Gnabry back towards him, Alba plays the ball back inside (in the opposite direction to the Germany defensive shape and movements) to Pedri.

Secondly in the image above, you can now see the full Germany 4231 defensive shape and how the whole team are over in the Spain left-hand side of the pitch. It is worth noting that maintaining a compact out of possession shape is an intended tactic of Germany - so not suggesting Spain's play has solely caused this nor Germany are out of shape at this point- but that Spain were more trying to provoke, manipulate and exploit this Germany intention with passing combinations and overloads on their left-hand side, before switching to the Germany weak-side (Spain right-hand side / Germany left-hand-side). For the first-time in this series of images, above you can also see Olmo's position for Spain, high and wide on the left flank (circled in top right of the image). Olmo's positioning in this build up is key as he is pinning the Germany right fullback (Kehrer) from jumping up to engage a) Alba when he tries to carry the ball up the touchline and b) Asensio when he drops, meaning Sule is required to, which creates a gap in the Germany backline. In this specific game Olmo exploited this space in the backline multiple times.

Anyway, to conclude this sequence, in the final image below, you can see Pedri shaping to switch the play to their right-hand side (Germany's left, and now weak-side). On this right-hand side for Spain, Carvajal is free (who Pedri actually passes to) but you can also see Gavi's position on the outside, and with space to exploit behind, the Germany midfield line.

All of the aforementioned movements, passing combinations and numerical overloads in the sequence above were a clear demonstration of how Spain were aiming to build possession from the back via their left-hand side, before switching to their right-hand side where they would have players, ready and waiting in space to try and exploit Germany on their now weak-side.

Before moving onto the next example, note in the final image above how many players Spain have on their left-hand side (six in total, if you don't include Gavi). This specific point is not to remark on any numerical superiority (which if you were to just crudely count in the image above would not apply) but more so to reference how Spain players not directly involved in this sequence, namely Olmo and Busquets, still played an important role with their positioning to help manipulate the Germany players / high block into the areas that Spain wanted to them to be in.

And this reference nicely leads onto the second build up example from Spain in this game. Where again, they played out via their left-hand side to draw Germany up and over, before switching to the right-hand side to exploit the space on the right-hand side. However, in this example, there is a more visible impact of how Busquets off-ball movement helped create space that Spain could then exploit.

In the first image of the sequence below, the ball is again with the Spain goalkeeper (Simon) and he actually stands still with the ball to try and provoke an engagement from Muller, and once he gets the reaction he's trying to instigate (a movement towards him), he plays the ball to Laporte to initiate Spain's build up on their left-hand side. Note - a key feature of this sequence, is Busquets movement towards the Spain right-hand side to drag Gundogan (player covering him) wider and therefore creating space for Pedri to drop into. Whilst subtle, this type of movement from Busquets perfectly sums up how even without touching the ball, he plays a key role and responsibility in Spain's build up play.

In the next image below, you can now see Pedri in shot as he's dropped into that pocket of space Busquets helped create. Laporte is about to make a pass out to Alba who, like in the first example, has dropped deeper and wider to a) make a passing angle for Laporte but also b) draw up and over the Germany high press. Also note Gavi in the image below, again, he is beginning to advance higher up the pitch in the inside right channel, ready for the potential (and eventual) switch of play to the right-hand side.

As per the first build up example, due to Spain playing out from their left-hand side and trying to pull the Germany high press / block up and over, Asensio (circled) can again drop into pockets of space behind the Germany midfield line (i.e. Kimmich) following their attempts to press, to offer a vertical passing lane from that deep left flank area. Also note how Olmo (also circled) has dropped to offer a line pass but has quickly changed direction and begins to make an opposite movement back up the line to exploit the space in behind.

After Asensio receives the ball, he control and protects it, carrying it back into Spain's own third which draws Germany players too him and then he finds a pass inside to Pedri.

By the time Pedri controls the ball, Busquets has made a dart into the vacant area of space, on the blindside of Gundogan (who due to Germany's attempt to press and stay compact as a unit has been drawn over to where the ball is, thus leaving Busquets unmanned), to receive the next pass. This movement from Busquets for the next pass gives Goretzka a decision to make - jump up and potentially leave Gavi (who whilst he's not directly marking, is at least trying to cover by staying goal side of) in space or allow Busquets time to control the ball and have the option of making an unopposed forward pass.

In the next image below, you can see that Goretzka is forced to jump up and try and engage Busquets (and he nearly wins possession). But Busquets manages to poke the ball out to Gavi who is then in lots of space on the right-hand side to turn and begin running at the Germany backline.

And in this final image, you can see why it's called the 'weak side'. Spain's right winger, Torres, has been maintaining height and width on the right flank so is a) in space out wide to receive the ball but also b) has lots of space to run in behind the Germany backline too. Gavi's carrying of the ball gives the Germany backline an issue as when to go and engage.

Whilst the two build up examples provided did not necessarily result in direct goal scoring opportunities (Germany recovered well in the second example), they did demonstrate ways that Spain were able to progress possession from their own third, into the middle and final thirds where they could then initiate their possession and attacking tactics in those phases.

In middle third possession, as mentioned, once Spain had controlled possession, they could vary between a 4-1 base with a staggered forward line of five, and also a 2-3 base with a staggered forward line of five. Here are some examples of Spain in these two respective structures across their four World Cup games (click to enlarge).

Note, the 'middle third' section of the pitch can mean different things to different people. For the purpose of this post, my reference to the 'middle third' is once possession has progressed from Spain's own third and into either the top of the Spain half, the halfway line area or just inside the oppositions half.

As highlighted earlier in the post, the difference between these two bases were very subtle and, at times, could be argued either way. Therefore, the above screengrab examples are not intended to suggest that these were the only structures Spain played in those respective games, in middle third possession, but instead to show visually how these structures looked in real-life scenarios.

However, whilst there is an acceptance that a 2-3 base and 4-1 base could be argued either way - especially during an ever moving football match - there did seem to be a clear intentional difference in what horizontal line the Spain fullbacks played on (whether closer to the centre backs or midfield pivot) depending on the opposition's out of possession set-up and pressing scheme(s).

Even though Spain's middle third possession structure would transition in-game, I would argue that their predominant middle third possession base structure in each game were:

vs Costa Rica = 4-1 base (so their fullbacks positioned on a horizontal line nearer their centre backs with their single midfield pivot ahead)

vs Germany = 2-3 base (so their fullbacks positioned on a more advanced horizontal line than their centre backs and nearer to the single midfield pivot)

vs Japan = 4-1 base (so their fullbacks positioned on a horizontal line nearer their centre backs with their single midfield pivot ahead)

vs Morocco = 4-1 base (so their fullbacks positioned on a horizontal line nearer their centre backs with their single midfield pivot ahead)

Below I have provided my assumptions on the reasons (emphasis on the plural) as to why I think there was a difference between a 4-1 and 2-3 base, and why they chose to predominantly use that respective structure in each of their games, based on the opposition's out of possession set-up (and pressing schemes).

In the games against Costa Rica, Japan and Morocco, these opponents were more passive without the ball and preferred to drop into a compact mid-block defensive shape which prioritised restricting the space between-the-lines that Spain's players could move into and receive in.

These opponents used their forward line's cover shadow to block passes into the Spain single midfield pivot (let's just call him Busquets). By doing this, the opposition could allow their midfield line to sit deeper, more compact to their defensive line, and focus on blocking forward passes in to any Spain players between-the-lines e.g. the two Spain advanced central midfield (or 8s if you prefer), Gavi and Pedri.

These opposition midfield lines could also, at the the right time, jump up and engage the Spain player on the ball from this mid-block shape, knowing that any space they vacate behind them will be mitigated by the overall team's compactness (i.e. a teammate will be in close proximity to cover).

My assumptions therefore as to why Spain predominantly used a 4-1 base to counter these out of possession set-ups, are as it allowed them (in possession) to:

push Busquets onto a higher horizontal line, thus pulling the opposition's forward line (and therefore rest of their defensive block) deeper, and allowing Spain more space, and less opposition, to progress the ball into, and through, the middle third

exploit the fact that Busquets was on the blindside of the opposition forward line, as on the times he did receive the ball, he could then draw out an opponent from the midfield line which created space for others to exploit in behind this

have four players in front of the oppositions defensive block where they could easily circulate the ball from side-to-side, stretching the opposition, patiently trying to find / force gaps to make forward passes in to

use the additional players in their base of four to provoke the opponent to jump out of their position to engage, and therefore leave space in behind which can be exploited (Spain did this by using a) their fullbacks drawing out the opposition wide midfielders and b) their central defenders carrying the ball forward to entice an opponent up and out)

In the game against Germany, Spain faced a 4231 defensive block which tried to press and engage them higher up the pitch. Gundogan, the central player of the three behind Muller, was tasked with staying close to Busquets, on Germany's goal side. In Germany's mid-block, Muller would at times assist Gundogan in covering Busquets, with both players able to pivot off him whilst the other goes to engage the Spain central defender on the ball. The roles of the players wide of Gundogan, Gnabry and Musiala, in a mid-block were to block passes into the half-spaces and get out to the Spain fullback on their side when in possession.

In this 4231 defensive block, Germany had more defensive lines for Spain to play through and this structure allowed them to match up to Spain's in possession structure, in essence, each player having a direct opponent to cover with the exception of one minus up front (Muller versus two central defenders) and one surplus in defence (two Germany central defenders versus Asensio).

My assumption therefore as to why Spain predominantly used a 2-3 base to counter this out of possession set-up, are as it allowed them (in possession) to:

position their central defenders and fullbacks on different horizontal lines, offering different passing angles to bypass the two Germany forward lines (Muller being the first forward line and the three in behind being the second)

position their fullbacks on the outside of the Gnabry and Musiala which is addition to being linked to the point above also meant that when the fullbacks received the ball it would draw a Germany player out towards them, thus moving the Germany block to try and create space elsewhere that can be exploited

allow Busquets to make his intelligent off-ball movements to help drag Gundogan (and at times Muller) out of areas where Spain wanted to play into e.g. through central areas of the pitch (whereas in the 4-1 base, Busquets tended to drag opponents deeper, in the 2-3 base, he tended to drag opponents higher and wider out of central areas)

position the fullback on the Germany weak side, on a higher horizontal line to better exploit switches of play opportunities e.g. if Germany had squeezed over to the Spain left-hand side, then Carvajal being higher meant then when we received a switch, he was better positioned (closer) to exploit the spaces in advanced areas

In each of Spain's four games their opponents had slightly different mid-block pressing schemes. But without going into the intricacies of all of these, ultimately when Spain had possession in the middle third, regardless of whether it was a 4-1 or 2-3 base, they tried to provoke, manipulate and manufacture gaps in the opposition defensive block to work the ball through, around and/or over the opposition to advance possession to their forward players in the final third.

As mentioned, Spain would have a staggered forward line of five in middle third possession, with two wide players holding width and playing up against the opposition backline, Pedri and Gavi (two 8s) tending to play deeper in the half spaces, both dropping in front and in behind the opposition midfield line, and Asensio as the highest central player, making both runs in behind and coming short to receive the ball in pockets of space between-the-lines, often to help make a midfield diamond and offer numerical overloads in central areas. The roles described were the predominant positions these players played but within this structure there were also lots of positional interchanges and nuances which will be covered later on in the post.

Finally, from a general in possession structure point-of-view, when Spain progressed the ball into the final third they predominantly played in a 235 structure, with a flatter forward line of five. This shape would involve all of their outfield players being positioned in the oppositions half to help maintain and sustain possession, and also be primed to counterpress in the event of a turnover. As so many players high, and within the opposition's half, Spain were always in close proximity to quickly put pressure on the opposition following a loss of possession.

The structure of their 235 shape also allowed for a pretty standardised rest defence set-up, with players behind the ball and goal side of the oppositions highest positioned players, and players packed into central areas, able to go and engage opponents on the ball following a turnover - in essence trying to prevent opposition attacking transitions at source. The profile of the Spain players allowed them to do this, in particular the energy of both Pedri and Gavi.

Like in middle third possession, but even more so in the final third, there were lots of positional interchanges within this structure and attacking tactics used to try and disrupt the opposition and create goal scoring opportunities. The key features of these will now be covered in more detail.

Positional Interchanges

When Spain had the ball in the middle and final third, within their in possession structure they would execute a number of positional interchanges in attempt to disrupt the opposition's defensive set-up. Players would change positions within their structure, often simultaneously, in attempt to 'confuse and lose' their opposition marker / player covering them.

The aim of these positional interchanges was that these movements of the Spain players would drag (move) the opposition out of / away from their defensive role or position in the team and therefore create a gaps in their system that Spain could then exploit. This disruption of the opposition only needed to be subtle, it could either be a moments hesitation in the opposition of who was supposed to be marking / covering who, or simply an opponent being pulled higher or wider across the pitch which created a new pocket of space that a Spain player could receive or pass the ball into.

The types of positions that would interchange within the Spain in possession structure were; fullbacks and the wingers, fullbacks and the 8s, and wingers and the centre forward. This is not to suggest that other positions within the Spain structure could not interchange, there was an element of organic fluidity within the whole team, but the aforementioned positions were clearly predetermined and constantly repeated interchanges across all games.

Spain executed the majority of their positional interchanges - and what this section will showcase - on their left-hand side. The right-hand side could interchange but it was less frequent and not a recurring pattern across all of their World Cup games, only mainly executed versus Morocco. This bias of the positional interchanges being skewed to the left-hand side also links to following section of this post, asymmetrical positions and varied roles.

But back to positional interchanges and time to describe and showcase multiple examples of how Spain used this on their left-hand side throughout the tournament - and what benefits it gave them.

On Spain's left-hand side, their most common positional interchanges involved their left fullback (mainly Alba), left winger (Olmo) and left 8 (Pedri). In the middle and final thirds, these players would most commonly interchange with Pedri dropping to a deeper left half space, Alba advancing to a high and wide left flank space and Olmo coming infield to an advanced left half space area - when in this position, Olmo could then also interchange with Asensio as the centre forward.

In addition to these interchanges being executed as a result of the general reasons highlighted above, it also suited each of these three players characteristics and helped play to their strengths:

Alba was able to play more as a winger, advancing higher up the pitch and receiving the ball often on the outside and against the last line of the oppositions defence, where he could try to beat his opponent 1v1 and put in crosses to the box. During the World Cup Luis Enqrique descried Alba as the "the best winger in the world in the last third of the field". Alba generated 3.75 shot-creating actions per 90 during the World Cup, according to FBRef.com, Spain's highest of any player.

Pedri was able to drop deeper and get on the ball more, in front of the oppositions defensive block, where he would have more time and space in possession to help dictate play and try and find penetrative passes, in particular using his right footedness for both reverse passes and clipped balls over the top of the left-hand side of the opposition defence. Despite only playing 4 games, Pedri had the 13th highest amount of touches at the World Cup according to FBRef.com and the 9th highest in the middle third, he had the second highest amount of touches for Spain after Rodri who was first for total touches in the whole tournament - now this is skewed due to Spain's high possession but it's more highlighted to help demonstrate how Spain wanted Pedri on the ball more, he had 462 touches compared to Busquets 309 and Gavi 183.

Olmo was able to use his ability at finding, and then receiving the ball, in more advantageous centrally aligned pockets of space between-the-lines where he could then make a final pass in behind the opposition or shoot himself. Olmo actually generated the highest number of shot-creating actions (SCA) for Spain at the World Cup with 12 (but played more minutes than Alba) so averaged 2.94 SCA per 90. He also had Spain's highest number of shots in the tournament with 12 which generated a total xG of 1.4, again Spain's highest of all their players (all stats are according to FBRef.com).

Below are multiple visual examples of these players positional interchanges across all four of their World Cup games.

(Slight) Asymmetrical Positions (and varied roles)

Whilst Spain's predominant in possession structure was quite symmetrical with fullbacks, the two 8s and wingers mirroring each other's position by playing on similar horizontal lines - as per the standard principles of positional play, ensuring players are always occupying certain zones / areas of the pitch - to further disrupt the opposition, and mostly in conjunction with the positional interchanges described above, Spain could at times position their fullbacks, 8s and wingers slightly asymmetrically, not necessarily all at the same time nor too stark. And in addition to this, Spain could also vary these players respective roles.

Below are examples, across each of their games, of Spain's in possession structure in perfect symmetry. See how the fullbacks, two 8s and wingers are all positioned on similar horizontal lines.

Now here are alternate examples, again across their four games, of how Spain could vary their in possession structure with the use of slight asymmetrical positioning of these players (mainly their two 8s). As mentioned, this asymmetrical positioning was often not a stark contrast, more a subtle altering of players horizontal lines (in front and in behind opposition lines).

The examples above were the most commonly used execution of this asymmetrical positioning, and it generally consisted of Pedri (left-sided 8) dropping deeper in front of the opposition midfield line whilst Gavi (right-sided 8) positioned himself behind it. But other examples of this included, at times the ball side fullback for Spain advancing higher with the opposite fullback sitting slightly deeper to protect their weak side (not a hard rule as there were exceptions), and Olmo (left winger) with more license to come infield compared to Torres (right winger) who predominantly held the width on the right flank.

Due to the profile of players selected in the Spain squad, replacements and substitutes for the aforementioned players shared similar characteristics so the positions and roles of the players remained the same regardless who playing e.g. Balde for Alba, Williams for Torres and Fati for Olmo.

In addition to asymmetrical positions of the fullbacks, the two 8s and wingers, the players within these 'same' positions also had varied roles for the team.

Fullbacks: the left fullback (Alba or Balde) tended to be more advanced and get involved in the attacking play compared to the right fullback (Azpilicueta or Carvajal). As mentioned, this is likely due to the profile of the fullbacks but also the set-up of the team e.g. wanting the left fullback to push high to allow for the positional interchanges on that side of the pitch. So whilst it was the left fullbacks role to help provide width in the final third, get behind the opposition defensive line and put crosses / passes into the box from that area, the right fullbacks role was to support play in all possession phases, by offering a back-up pass to help recycle / maintain possession, put in deeper crosses from the wide and insight right channels, be positioned behind the ball to help cover defensive transitions and help execute the counterpress.

Two 8s: whilst both Pedri and Gavi could at times play similar roles i.e. getting behind and in between the opposition midfield line to receive passes between-the-lines, Pedri tended to drop deeper more in front of the midfield line (and often, the whole opposition's defensive block) to get on the ball more and help Spain maintain and progress possession through the thirds, Whereas Gavi predominantly positioned himself in the right half-space pocket between opposition defensive and midfield lines to receive passes and also make runs beyond the defensive line, in between the left-sided centre back and left fullback / wingback (more on this in the section below).

Wingers: the right winger tended to hold the width more on the right flank and predominantly tried to attack his opponent on the outside, whereas the left winger came infield more, into the half-space, trying to receive the ball between-the-lines, and also at times interchanging with the centre forward (Asensio or Morata). Again, this decision is likely impacted by the profile of the wingers but also due to the profile, and roles, of the fullbacks on their side e.g. left fullback tended to push up higher and attack on the outside so this meant the left winger had license to come inside.

All of Spain's slight asymmetrical positioning and varied roles was interlinked with the profile of the players in their squad (i.e. it's what suited them), it supported how the team were set-up and wanted to play (e.g. allowed them to get numerical overloads and execute their positional interchanges, in different phases of play) and it allowed them to vary their attacking play to a) try and disrupt the opposition and b) offer different threats on different sides of the pitch.

In reference to the last point above, about Spain being able to have different threats on their right and left-hand sides...

On Spain's left-hand side they tried to use positional interchanges (rotations) to disrupt the opposition e.g. the left fullback, left-sided 8 and left winger would all swap positions to try to 'confuse and lose' their markers, thus creating potential gaps that they can exploit. Plus, these interchanges suited each player, once they changed position.

On Spain's right-hand side, the right fullback, right 8 and right winger were more static in their positioning but this, when complimented with everything else Spain were doing, including what was happening on the left-hand side, could help create overload and switches of play opportunities on that flank. For example, following a spell of possession on Spain's left-hand side, the right fullback or winger could be in lots of space on the right flank for a switch of play or Gavi's positioning in the right half-space pocket would help pin / occupy some of the opposition players which would help create space elsewhere for a teammate e.g. the opposition left fullback wants to stay tight to his left-sided centre back to restrict space between them that Gavi can run into, therefore they allow extra space on their outside for the Spain right winger to receive the ball into.

This point about Gavi's positioning and role for the team nicely leads into the next section of the piece, about how Spain utilised his off-ball runs / movements in their possession and attacking play in each of their games.

Gavi’s Off-Ball Movement

Gavi started all four of Spain's World Cup games and played a total of 284 minutes, out of possible 390 minutes, being subbed in three of the games around the 65th minute mark. As described in the post, he played as the right-sided 8 in midfield and had a specific role for the team, predominantly positioning himself between the opposition defensive and midfield lines in the right half-space.

Now whilst Gavi took up this position to try and receive passes between-the-lines to then carry the ball, make another pass or shoot himself, he also had another key role - his off-ball movement. From this position, in the middle and final third, Gavi made numerous off-ball runs in between the oppositions left-sided central defender and left fullback / left wingback.

On face-value, the objective of these runs appeared to be to receive the ball in behind (or at least to give the option for that pass). A specific trigger for this run was when the opposition fullback was pulled wider towards the right winger and therefore vacated space that Gavi could exploit. However, on closer observation these off-ball runs to provide depth also appeared to be, at times, used as an intentional decoy, in order to create space for others / the team by dragging the opposition backline or specific opponents deeper and/or from certain areas.

Here are examples from every game to help showcase these observations. The amount of examples provided is intentional, to highlight this being a key tactical feature of Spain's attacking play. In addition to the visual examples, explanations for each have been provided as to the benefits, and outcomes, these off-ball runs provided the team.

Inside Horizontal Passes

Decoy runs between and beyond the opposition defensive line were not exclusive to Gavi in the Spain team. The tactic in itself was a recurring theme of Spain's attacking play in the final third. Spain used this tactic to try and create space for players to receive the ball from a horizontal pass in central areas, specifically in and around the box, for either a shot or subsequent attacking action, following a decoy run behind to drag the opposition deeper / away from a specific area.

Here are some examples of Spain repeatedly using this tactics across their four games. Descriptions of the movements and outcome of each of these examples has been provided.

vs Morocco

In their Round of 16 game against Morocco, Spain were eliminated on penalties following a goalless draw. Whilst Spain had 68.4% possession (according to FIFA), they will be disappointed (and were criticised for) the fact they only managed one shot on target, 13 shots in total, in 120 minutes of play.

A lot has been written on Morocco's out of possession organisation, including their predominant compact, mid-block shape with their midfield 8s pushing up to engage centrally, with their wingers sitting deeper to support their fullback and block passing lanes into the half-spaces - and then when required, those respective players switching roles, so the 8s dropped to cover when a winger pushed higher to engage. Due to wanting to play a compact shape, to restrict space between-the-lines, Morocco's defensive line was not exactly sat on the edge of their own box when defending, instead pushing up to stay close to their midfield line. (If you want to read more on Morocco out of possession, I suggest checking out Ahmed Walid's pieces in The Athletic, if you subscribe that is.)

But to put the focus back on Spain, I think the knowledge of this potential space in behind the last line of the defence influenced their decision to start with Marcos Llorente, in what were his first minutes at the World Cup, instead of their more orthodox, and previously used, right fullbacks, Azpilicueta and Carvajal. Llorente's physicality and playing style, suited the idea of attacking vacant space from deep. And as will be shown in this section, Spain had a plan to use this skillset, even from his initial right fullback starting position.

Spain set out to play in the same manner as their previous games. As Morocco preferred to get into a mid-block defensive shape, Spain were easily able to progress the ball into the middle third. In this phase of the pitch, due to Morocco using their forward line's cover shadow to screen Busquets, Spain's in possession structure tended to be formed with a 4-1 base.

With the ball, Spain continued to execute their usual style of play and attacking tactics e.g. positional interchanges and off-ball + decoy runs beyond to create space etc, with their standard objectives of trying to provoke, manipulate and manufacture gaps in the opposition defensive block to work the ball through, around and/or over the opposition to try and create goal scoring opportunities.

But some new tactics employed by Spain in this game, as already alluded to, involved positional interchanges on their right-hand side to get Llorente higher up the pitch, where he could then try and attack the space beyond the Morocco last line of defence.

In the image below there's an example of Spain executing this tactic after 5 minutes. Gavi has dropped deeper which has allowed Llorente to advance into the right half-space to attack the spaces between the Morocco left fullack and left-sided central defender, once Torres received the ball out wide.

Now, this didn't mean Spain stopped using their previous inside right runner in behind, Gavi, in this game. Below is an example of how Spain executed two of their recurring tactical features - Gavi's off-ball movement and inside horizontal passes - around the 15th minute mark which nearly created a shooting opportunity for Asensio on the edge of the area.

In the above example, the sequence involved Gavi making a decoy run beyond, after Torres receives the ball out wide, which drags both the left-sided central defender and midfielder deeper. Following Gavi's run, Torres makes an inside horizontal pass to the now vacated space on the edge of the area for an incoming Asensio - but, unfortunately for Spain, the pass gets snuffed out by the Morocco defender.

Other examples of Spain recognising, and attempting to exploit, the space behind the Morocco backline are shown in the examples below.

In this first example, the image below shows how after 2 minutes Spain had already managed to execute their left-hand side positional interchange, getting Alba higher and up against the opposition last line of defence. In this action, Alba makes a clear offer to run in behind but Spain choose not to play the pass. But the immediate intent is clear.

In the second example below, again, Spain have executed their left-hand side positional interchange, getting Alba higher and up against the opposition last line of defence. This time, Alba's offer to run in behind is acted upon as Laporte clips a ball over the top of the defence but overhits it and it ends up getting swept up by the Morocco goalkeeper.

In the next example below, Spain generated their highest xG chance of the whole game, at 0.23 according to FBRef.com. In this action, Asensio makes a run in behind from his position between-the-lines which Alba sees, and then finds, with a perfectly executed pass. Asensio decides to shoot but misses at the near post - but he also had the option of passing into the box for an incoming Torres at the far post. Regardless of whether he chose the right option or not, it showcases how this specific tactic, when executed right, could create opportunities to score.

The next example below is nearly a carbon copy of the previous one. Asensio makes a run in behind which Alba spots and passes towards but despite the pass being good, on this occasion, Asensio fails to control and the ball squirms onto the Morocco goalkeeper. In the event of Asensio successfully controlling the ball, this chance - to my eye - would a have very likely generated a similar xG value chance as the previous.

All of the above examples were from the first-half - and it's not an exhaustive list - so whilst the stats will show Spain only had one solitary attempt on goal in the first half, suggesting a lack of proactive attacking play to breakdown the Morocco defensive block, the examples above help tell a different story.

Now before moving on, an additional observation to note in the image above is the positioning of Pedri, Gavi and Llorente. Now Llorente appears to be advancing up the pitch to take up his usual high, right half-space position, but instead of Gavi being deeper inside right, it is in fact Pedri. That is because around the 30 minute-mark, Spain switched the two, so Gavi became the left-sided 8 and Pedri the right-sided 8. This meant, that the Pedri would now interchange positions with Llorente instead.

This tactic was not a short-term variance in Spain's play either, it continued for the rest of the first half and into the second half, right up until Gavi was subbed on 63 minutes. Below are a couple of other examples of this tactic in action (click to enlarge).

My assumptions as to the reasons for this tactic, feel too simple but they are - 1) whilst Spain wanted Llorente to attack behind from this advanced inside right position, they didn't want to compensate for that by having Gavi deeper so this allowed both to play between-the-lines, and still allowed for Pedri to drop deeper to get on the ball more, and 2) it might have been used as an element of surprise, as Spain had not played in this way previously during the World Cup so Morocco will have not prepared for it (?)

Following that quick interlude to observe an interesting tactical feature, let's get back to focusing on the what Spain were doing to try and score. Above I have shown what Spain tried to do in the first half, and despite only registering one attempt on goal in the stats, Spain's tactics were causing Morocco issues, and barring some misplaced passes and touches, Spain were close to creating more openings.

So now let's focus on the second half. After the break, apart from an Olmo freekick on the 54th minute, Spain didn't have another attempt on goal until a wild shot from outside the area from Olmo again, on the 78th minute. These stats, again, do not reflect great on Spain's attacking play, but compared to the first half, they do represent a more accurate reflection of Spain's play.

In the second half, Spain were a lot more cautious with their passing. They appeared to take less risks, instead preferring to keep possession and patiently wait for potential openings to appear - perhaps, also fearful of surrendering too much possession and being counter-attacked on. I appreciate this patient approach is part of Spain's identity, however, at least in the first half of the second half, Spain could have afforded to risk turning over possession more, especially in the final third. Spain's play in the second half, in essence, became quite predictable.

The above point also links into this one - despite Spain's runs beyond the Morocco backline appearing to be a potential route to success in the first half, apart from a couple of occasions, these were non existent for the majority of the second half. It is worth pointing out that, as time ticked by in the game, Morocco dropped deeper, and thus limited the space Spain had to run into, let alone try and find a pass into. But Spain did actually attempt a few more passes in behind in the last 10 minutes of the game which ironically generated more threat and caused panic for the opposition, but as Morocco were so deep they always had bodies to help cover / recover the situation. It's all 'ifs, buts and maybes' but I can't help that think more of the same from the first half was required, at least in the early stages of the second half.

Other issues for Spain in the second half were - and this is nitpicking - for the first 25 minutes of the half, Olmo tended to maintain his position as a left-sided winger, with Alba often deeper. This was likely a result of wanting to position Gavi in that left half-space pocket, but as a result, it meant that when Olmo received the ball wide, his natural next movement was to come inside, and therefore into lots of traffic. This made it easier for Morocco to defend, and instead, perhaps Alba attacking on the outside of the Morocco block could have offered a different / better threat.

It would be remiss of me not to mention how - to a man - Morocco were relentless, and effective, in their defensive duties in the second half. Any potential gaps in their block that Spain were hoping to patiently manufacture were few and far between. And on the few occasions Spain looked like they might have gotten through, a Morocco player was their to put in a decisive tackle or block to quickly dampen that glimmer of hope.

Also, whilst Morocco did not create any attempts on goal in the second half until the 86th minute, they did execute their attacking transitions more frequently, and successfully. By successfully, I mean they managed to have spells with the ball, reducing Spain's constant control, and dragging Spain back towards their own half. This factor only added to the frustration of Spain in the second half and extra time - where both team's had opportunities to win the game before the lottery of penalties.

To try and wrap up this section, and game, most of what was stated above is what actually happened, with a few observations and thoughts on what Spain could have done differently sprinkled in. It is obviously easier with hindsight to try and highlight what else Spain could have done to score in this game - and even easier to hypothesise - but I think it's important to state that even after watching the game back, trying to breakdown 10 opposition players is very difficult. Spain have their way of playing, and in my opinion, if they played that game another 10 times, they would win the majority.

But my biggest frustration in this game, is that in the first half, Spain had good variety to their possession and attacking play. Whereas in the second half, before the last 10 minutes at least, Spain seemed too stuck to their very core principle of 'don't lose the ball'. They appeared to abandon all of their other tactical features which had previously served them well in during the tournament, by helping provide their play, and attacks, with variety.

Conclusion

To conclude this deep-dive, some of the post World Cup analysis on Spain, in my opinion, has played into the cliché narrative of them overplaying, having possession for the sake of possession, and not being able to mix up their attacking play.

Whilst I think versus Morocco, as detailed above, there were some aspects of their play that Spain could have utilised more (feels more apt than improved, as who knows whether it would have changed the result or not), my overall personal opinion of their 2022 World Cup, following close observation during, and re-watching after, is that the outcome bias of their exit had a factor in overshadowing all of their good work in previous games.

I appreciate the latter half of the previous sentence may raise the eyebrows of some, considering they only won one of their four games in Qatar, but to play into a cliché narrative myself, football - in particular, tournament football - is a game of very fine margins.

To highlight these fine margins;

vs Germany: Laporte carelessly, and uncharacteristically, gives the ball away in build up play which subsequently leads to Germany gaining possession in the final third and then equalising

vs Japan: following a dominant first half performance, Spain concede an equaliser as a result of a keeper error (should have saved) and then quickly go behind following a rather contentious goal - despite probing to get back into the game due to the game, and group stage state, both team's seemed rather content with the scoreline as it was

vs Morocco: granted it was probably Spain's overall poorest performance in the competition, and this was a result of a) the reasons stated above and (b) likely the bigger factor) Morocco being a resolute and a well organised side, but having said that, Spain didn't lose the game, they exited via the lottery of a penalty shootout

To therefore use Spain's style of play and commitment to their principles as the reason they did not progress further in the tournament, when it was that style of play and set of principles which helped them control the majority of periods in all of their games, to me is contradictory.

I also feel that if Spain had scored an undeserved / scrappy goal in that game to progress against Morocco - or even better yet, actually won the penalty shootout (!) - and then subsequently went out to Portugal in the Quarter Final, their post World Cup narrative would be a lot less noisy and negative. But that's all hypothetical.

I appreciate not everyone is a fan, or believer, of this highly orchestrated, positional style of play, but notwithstanding this (or opening up that debate or even sharing my own views), it cannot be argued that Spain set-up with a clear identity in Qatar, and as this post has hopefully showcased (at least with the ball, although key aspects of their play without the ball have been referenced too) is in addition to having their set in possession structure, player roles and attacking tactics, they had a variety of solutions to enforce their identity, offensively, on different, and all, opposition.

And whilst ultimately I appreciate Spain's World Cup story, to many, will have only compounded the cons and the naysayers of their style of football - to me at least - it did not undue all of the interesting, and admirable, tactical aspects of their play. I enjoyed watching their World Cup story, and I hope you enjoyed reading this tactical story too.

Thanks for reading.

All stats used in this post were obtained from either FIFA post match reports or FBRef.com and game screengrabs were captured from BBC iPlayer and ITVX.

Comments